Introduction

The group now known as Islamic State Mozambique (ISM) emerged as an armed group in October 2017, known locally both as al-Sunna wal-Jamma (ASWJ) for its ideological underpinnings and al-Shabaab for its extensive use of violence. Despite its rapid growth up to 2021, it has been one of the Islamic State’s (IS) most opaque affiliates. ISM was first recognized as a distinct IS province in May 2022, having previously been under the broader Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP) organization from as early as 2018. The origins of ISM lie in East African Salafi-jihadist networks that reached into northern Mozambique as early as 2007.1 This profile examines the group’s origins and its development over the past decade. It uses ACLED and other data to assess the group’s objectives and consider its future prospects.

Origins

ISM arose from Wahhabi-inspired religious thinking that challenged mainstream Islamic leadership, traditional norms, and state legitimacy. In its earliest form, the group developed as young, radical, and often well-traveled figures preached against state involvement in Muslims’ lives, condemned mainstream religious leadership, and challenged everyday social norms. Radicalized groups willing to take up arms and established in this way in mosques and madrasas would go on to be the core of the insurgency.2 The formation of such groups occurred across Cabo Delgado province in the 2010s. Mocímboa da Praia was the epicenter, but these groups were also found in Balama and Chiure in the southwest and south,3 Macomia on the coast, Nangade in the north of the province, and Niassa province to its west.4

This process of organization, the underlying ideology, and its challenge to accepted norms and authorities led to conflict within communities and between the group’s adherents and the state in the years prior to the insurgency. In Chiure in 2016, for example, it led to three days of conflict. While this conflict was initially within the Muslim community over authority with mosques, it was followed by a clash between sect adherents and police.5

Outside Cabo Delgado, similar processes of organization in Muslim community institutions were followed by the formation of armed groups, some of which had connections to Cabo Delgado and elsewhere in East Africa. This process was seen in neighboring Tanzania’s Tanga region between 2012 and 2017, where such groups had connections to Somalia.6 In Kibiti district of Tanzania, south of Dar es Salaam, mobilization in radical mosques and madrasas of hundreds of youth culminated in a proto-insurgency in 2015, which carried out two years of targeted killings against the ruling party and local government officials.7 The proto-insurgency was eventually put down in 2017 by Tanzania’s security forces, but key leaders of the insurgency fled to both northern Mozambique and northeast Democratic Republic of Congo.8

Parallel to the seeding of the insurgency was the emergence of Mozambique’s first liquefied natural gas (LNG) project near Palma town after considerable natural gas resources were discovered offshore in 2010 by the oil company Anadarko. Development of the LNG project was quick by international standards. By 2014, a decree law was passed to facilitate the project. By 2017, plans were being made to resettle affected communities, with approval of the project’s development plan coming in 2018. In 2019, two years into the insurgency, France’s TotalEnergies acquired Anadarko, and announced the project’s Final Investment Decision the same year.9 The fast-developing project would soon become a target of the group locally, the subject of IS rhetoric internationally, and the clearest demonstration of the group’s threat to the state.

Activity and Area of Operation

Years of organization in northern Mozambique, regional support networks, and an emerging LNG project would each factor into the shape of the insurgents’ activities, and the national and international response. The strong organization of insurgent groups and regional support networks enabled the rapid growth of the insurgency until 2019. The growth of the insurgents was followed by almost two years of consolidation between 2020 and 2021. During this time, the group did not control the province but ISM activity made it ungovernable. External interventions from Rwanda Security Forces (RSF) and the Southern African Development Community Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) severely disrupted the group. Despite the setbacks, ISM weathered these offensives until November 2022. Since this time, political violence carried out by the group has steadily decreased.

Growth: 2017-19

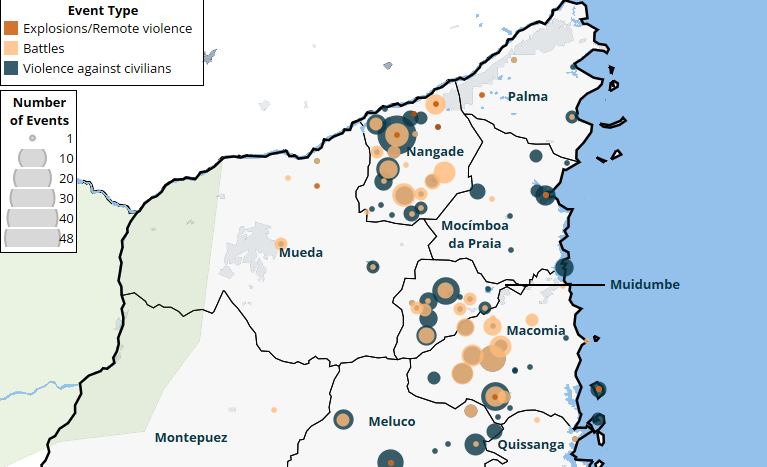

In the insurgency’s early years, the group was marked by a lack of a clear identity. The names ‘ASWJ’ and ‘al-Shabaab’ signaled violent jihadist ideology, but public messaging from the militants themselves was rare. An early video statement from January 2018 showed four young men addressing their “Mozambican brothers” and endorsing “Quran as law.”10 Nevertheless, the targeting of civilians by insurgents obscured any political objectives. From 2017 until the end of 2018, ISM had been involved in 66 incidents of political violence, of which almost 73% were targeting civilians. Over 80% of those incidents took place in the insurgents’ heartland of Macomia, Mocímboa da Praia, and Palma districts, with further activity in Nangade, Pemba, Muidumbe, and Quissanga districts. The targeting of civilians continued through 2019, accounting for 80% of annual political violence events involving ISM, as the group spread geographically. Over the course of 2017, 2018, and 2019, at least 464 civilians were killed by the group (see graph below).

Consolidation: 2020-21

If ISM’s political objectives were obscured, they first became clearer when formal affiliation of the insurgents with ISCAP was issued through IS media channels in June 2019. ISCAP, with the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) operating in DRC, at its center, had been acknowledged by IS in 2018. Relations between ADF/ISCAP with Cabo Delgado’s insurgent group predated June 2019 considerably. The United Nations Group of Experts has presented evidence of movement between ADF and Cabo Delgado’s insurgent group as early as 2017.11 However, affiliation with IS sharpened the Cabo Delgado insurgents’ ideology and would give access to both technical assistance and external financial support. This was clear in the subsequent coherence between operational targeting by the insurgents, IS analysis of the conflict, and local messaging within Cabo Delgado. Together, these three factors positioned the group with a clear ideology, challenging the state, focusing on local grievances, and targeting the LNG project.

In late 2019, IS had tasked IS Somalia, based in Puntland, to coordinate support across the region through its Karrar hub.12 Tactical training was provided reportedly as early as 2020.13 There is also evidence of payments to Mozambique as early as 2020, through the remittance of money raised in Somalia and South Africa and sent to Mozambique and DRC through agents in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda.14

The impact of IS support from Somalia became apparent in 2020 and 2021, permitting ISM to increase operations and allowing the insurgency to reach the peak of engagement in political violence events in June 2020. Insurgents pointedly targeted urban centers, seized control of Mocímboa da Praia town, and twice threatened the LNG project at Palma. By the end of 2020, their operations were concentrated in five districts in the north of the province and along the coast, with limited engagement as far south as Ancuabe and Metuge districts.

The authorities were, by this time, losing control of the north, with insurgents controlling the N380 and N381 roads. The former connects the provincial capital Pemba to Cabo Delgado’s northern districts, while the former connects the northern districts to Tanzania. In March 2020, Quissanga and Mocímboa da Praia district headquarters were briefly occupied. In April, Muidumbe headquarters was occupied,15 and in May, it was the turn of Macomia headquarters. These attacks culminated in August 2020, when the insurgents asserted control over Mocímboa da Praia town, expelling government forces. They went on to control the town for 12 months, until the arrival of the RSF the following year. The year ended with a series of attacks in Palma district, culminating in an attack on Quitunda on 1 January 2021, a village located on the perimeter of the LNG project that was built to house people evicted to make way for the project. The attack led to TotalEnergies ordering the evacuation of staff the following day (for more, see the following Cabo Ligado Weekly Updates: 25-31 May 2020, 10-16 August 2020, and 4-10 January 2021)

In all of these attacks, insurgents targeted state institutions such as garrisons, police stations, health centers, and schools. They also regularly targeted neighborhoods dominated by state employees and the homes of prominent figures in the ruling Frelimo party or business people.16 This shift to targeting state institutions was also reflected in a marked reduction in the proportion of times they targeted civilians. While civilian fatalities peaked in 2020 – reaching over 650 annual reported deaths amongst civilians – civilian targeting events comprised a smaller proportion of the overall political violence involving ISM in 2020 compared to previous years.

The shift in operations and targeting was indicative of an increased interest in taking on the state and undermining LNG investment. It reflected an analysis of the conflict presented by IS through its al-Naba newsletter in July 2020, which highlighted the role of “Crusader oil companies,” unspecified historical grievances, and abuses by the security forces against civilians during the conflict as factors justifying the conflict.17 Locally, a short statement by ISM filmed at the District Administrator’s office in Quissanga in March 2020 succinctly expressed its objective of taking on the state. “We don’t want the Frelimo flag … you can see that flag that we are using,” the insurgents said, under an IS flag.18

Dispersal and Contraction: 2021 to date

The al-Naba editorial in July also noted the likelihood of international intervention, which by that time was an ongoing agenda item for Southern African Development Community (SADC) leaders, with South Africa having started planning military support for Mozambique by at least May that year. The insurgents’ attack on Palma town on 24 March 2021 presented a real threat to the LNG project, and precipitated intervention from both SADC and Rwanda in July 2021.

Reflecting the importance of the LNG project to both the Mozambican government and to the insurgents, the RSF deployed in Palma and Mocimboa da Praia districts. The LNG project itself is situated in Palma district, while the port town Mocímboa da Praia is critical to the project as the commercial center of the province’s northern districts. Both districts had been closely targeted by the insurgents from the first day of the conflict. The RSF successfully gained control of both district headquarters by August 2021, less than two months after the initial RSF deployment.

SAMIM deployed more slowly, covering Nangade, Macomia, Mueda, and Muidumbe districts. However, a lack of coordination between the RSF and SAMIM forces allowed the insurgents to disperse. By the end of 2022, ISM had been involved in political violence events in new districts, and 16 of Cabo Delgado’s 17 districts overall, as well as parts of Nampula and Niassa provinces (see maps below).

Crédito: Link de origem

Comentários estão fechados.