Study area

We conducted our experiment in the Uruashraju glacier foreland located in the Quebrada Pumahuacanca within the National Park of Huascarán (NPH), Cordillera Blanca, northwestern Peru (Fig. 1). The Cordillera Blanca is the world’s most extensively glacier-covered tropical mountain range43. In the 1960s, the imminent extinction of the overhunted and emblematic vicuña, a native Andean camelid, prompted the creation of the NPH. This area is semi-arid and has highly seasonal precipitation with 80% of the 700 mm (~ 3500 m.a.s.l.) to 1000 mm (~ 4550 m.a.s.l.) per year falling between October and May44. The mean annual air temperature at 3450 m.a.s.l. is approximately 12–14 °C with strong diurnal variability45 but little seasonal variability due to its tropical location (9°S). The geology of the Quebrada Pumahuacanca is dominated by granodiorite and tonalite, with outcrops of the meta-sedimentary Jurassic Chicama formation, that consists of shale, pyritic siltstone, and quartzite with volcanics in some areas46. Sulfide-rich lithologies occur within the glacier foreland and their oxidation after the retreat of the ice is linked to low pH values47.

Location and study site set-up. Map of location with respect to the Santa River watershed (a), and Río Negro sub-watershed (b). Map of the experiment within the Uruashraju glacier foreland (c). The glacier retreat outlines were produced and provided by the ANA (Área de Evaluación de Glaciares y Lagunas, Autoridad Nacional del Agua, Huaraz) based on topographic field surveys of the glacier fronts since 1948, and analysis of photographs. Maps generated by authors with licensed software ArcGIS Pro 3.0.2 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/).

The Pumahuacanca Quebrada (from 4050 to 5605 m.a.s.l.) has patches of high Andean woodlands (e.g., Polylepis spp. and Gynoxis spp.), wetland ‘bofedales’ dominated by cushion-forming plant communities (e.g., Distichia muscoides), and grasslands dominated by tussock grass such as Cinnagrostis rigida48. Certain species like Werneria nubigena indicates the presence of non-native livestock and overgrazing. Within the NPH, Pasture User Committees (CUP) use these high pasture ecosystems to graze their livestock. This is the case of the CUP of Arwaycancha in the Quebrada Pumahuanca. In recent years, the uncontrolled introduction of exotic livestock for agropastoralism and tourism activity has caused degradation of pastures and the disappearance of some native species within the Park48. Due to their soft footsteps and prehensile split upper lips Andean camelid minimize impact on the groundcover compared with introduced livestock49,50. The NPH has thus supported camelid breeding initiatives as an ecosystem and biodiversity conservation strategy51.

The study site (77° 19′ 20″ W, 9° 35′ 47″ S) lies between 4680 and 4700 m.a.s.l. in a terrain deglacierized between 1979 and 199552 (Fig. 1). This research was in collaboration with the NPH and the Llama 2000 Asociación, a local community of farmers, who own the llamas. The farmers’ own village of Canrey Chico, Olleros has contaminated water due to acid rock drainage (ARD) that threatens their agriculture53. As an adaptation strategy to glacier retreat, the farmers aim to find solutions to increase the vegetation cover in recently deglacierized areas in order to reduce ARD. Previous floristic plot surveys carried on in the Uruashraju glacier foreland identified 47 vascular plant species (Zimmer et al., unpublished data; Table S3). We selected the Uruashraju foreland based on the Llama 2000 Asociación’s shared interest in our research questions, the presence of llamas in the adjacent Quebrada, data availability for deglacierization chronology, floristic comparisons within the overall glacier foreland (Table S3), and the ecological representativeness of the site. Considering the socio-geoecological aspects of the region, we expect our results to be generalizable to the overall Cordillera Blanca and, possibly, to other mountain ranges.

Context and experimental design

The Llama 2000 Asociación launched the Llama 2000 Project to increase the value of local llama breeding and conserve an essential part of their Inca biocultural heritage. In 2019, the community aimed to strengthen its activity promoting the sustainable management of llamas and vicuñas to develop community-based tourism along the Qhapaq Ñan trail, enhance local economy, and develop climate change adaptation strategies. We collaborated with the Llama 2000 community and the NPH to test a novel adaptation strategy to glacier retreat by introducing llamas in the Uruashraju glacier foreland. Manipulative experiments better predict the causal impacts of short-term ecological change and allow for a better control of confounding factors54, which here included livestock disturbance, llama stocking rate and visit frequency to the site, and camelid movement between Quebradas. Here, we are testing a novel adaptation strategy to glacier retreat by introducing llamas in a glacier foreland in a region where the density of Andean camelids has strongly decreased over the last century and where camelid breeding initiatives have been strengthened by National Entities (i.e., NPH and SERNANP—Servicio Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas por el Estado51).

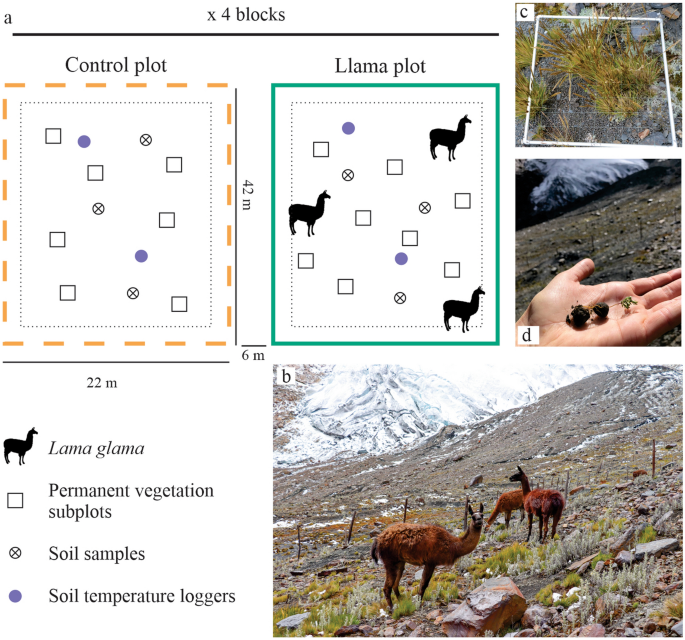

In June 2019 we set up a complete block design with four monitoring blocks—i.e., four llama plots and four control plots (Fig. 2a, b)—across a chronosequence since deglacierization: the south corner of the experiment was ice-free in ~ 1979 and the north corner in 1995 (Fig. 1c). We built eight plots (925 m2 each) over 12,500 m2 of low to moderate slopes. Within each plot, we randomly established eight (1m2) permanent subplots (Fig. 2c). Thanks to personal communications with the Llama 2000 farmers, specialists of the NPH, and a local zootechnician, we determined the animal load and grazing intensity within the plots based on (1) the natural density of vicuña observed in proglacial landscapes in the Cordillera Blanca (NPH, Unpublished data), (2) llama and vicuña behavior (herd grouping and displacement between altitudinal range), and (3) vegetation cover of the study site and llama nutritional requirements. These considerations allowed us to replicate a natural phenomenon (i.e., several proglacial landscapes have been identified as vicuña habitat within the NPH). From June 2019 and to 2022, in each fenced plot, three llamas grazed for three days each month (cf. Appendix 1 – Experimental design).

Experimental design and in situ surveys. Design of the experiment (a), Llama glama within a llama plot (b), 1m2 vegetation subplot (c), seedling germinated from llama feces found within the experiment in June 2022 (d).

Field data collection

To test the effects of llamas—grazing, trampling, and latrine behavior—on proglacial ecosystem development following our three hypotheses (i.e., soil enrichment, vegetation succession, and seed dispersal), we collected: (1) pedological, (2) plant diversity and productivity data, and (3) llama dung pile samples. The data collection took place at different times (Table 1).

First, in May 2019, before introducing the llamas, we conducted the first floristic and geomorphic evaluations of the 64 subplots (i.e., Hypothesis 2). At each subplot, we identified all the vascular species (Table S4). We estimated visually their relative surface cover, density, necromass, and their average height. As well, we recorded the presence of biological soil crusts (BSC) measuring their heights and relative covers. In each subplot, we also estimated soil granulometry —percentage cover of sand (< 2 mm), gravel (< 2 cm), rock (< 10 cm), and block (> 10 cm). Every year from 2019 to 2022, we replicated the same biotic and abiotic data collection for each of the 64 subplots to study the effects of the presence of llamas over time. In addition, in 2020, 2021, and 2022 we visually assigned a greenness index (0, 1, or 2) to each subplot based on the proportion of green vegetation within each subplot. During the field evaluation in 2020 and 2021 we observed the presence of eaten pasture within the llama plots, which could have biased our estimations of plant cover and height. To overcome this concern, in 2022 we waited three weeks between the last grazing treatment and our field evaluation, giving time for the plants to grow again after the grazing event. We also reported eaten pasture within the control subplots in 2020 and 2021, indicating either that the llamas escaped at least once from the fences, despite attentive care, or the llamas grazed within the control area during their arrival on site while the farmers were distributing the animals between plots.

In addition, we measured three plant functional traits: leaf dry matter content (LDMC), total nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P) to study plant productivity (i.e., Hypothesis 2). Plant leaf N is directly related to photosynthesis and respiration and reflects the trade-off between greater photosynthetic capacity and potentially suffering more herbivory55. LDMC correlates negatively with potential relative growth rate and positively with leaf lifespan56. Leaves with high LDMC tend to be relatively tough and are thus assumed to be more resistant to physical hazards (e.g., herbivory) than are leaves with low LDMC55. Therefore, LDMC is an indicator of a plant’s resource use strategy: usually, stress tolerant and slow growing species found in stressed environments display high LDMC and low N, whereas low LDMC and N-rich leaf are characteristic of competitors and ruderals with fast resource acquisition strategies55. For the trait measurements, we selected four species based on (1) their presence in the 8 plots (Table S4), (2) their potential as ecosystem engineers (i.e., Pernettya prostrata: slope stabilization; pers. obs., Senecio sublutescens: high litter production and micro-habitat creation; pers. obs.), and (3) their palatability (Agrostis. tolucensis; P. prostrata; pers. obs.).

In June 2022, we collected 10 leaf samples from different individuals of the same species within each plot. Each sample is a composite of a minimum of three individuals, summing to approximately 15 to 40 leaves per sample depending on the species. We used stratified sampling within the four llama plots, collecting half of the 10 samples from individuals located inside or down-slope of a dung pile and the other five samples from individuals located three meters outside of dung piles (cf. Appendix 1 – Field data collection). The collection of plant material and soil samples was conducted in accordance with relevant recommendations and authorizations of the SERNANP (licenses N°008–2019-SERNANP-JEF and N°005–2022-SERNANP-JEF). The soil samples were exported to the USA under the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) permit to receive soil P330-17–00,299 and P330-20-00161_20200706. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines. As importantly, because we measured and counted the same plant specimens present within the permanent subplots in the control and the llama plots every year, we did not collect the full plant specimens; the collection of plant specimen would have been destructive for the experiment and biased the floristic evaluations results for this study but also for the long-term monitoring of the experiment. Therefore, the plant species identified and studied have not been deposited in a public herbarium, since the registration process requires the full specimen (including vegetative material and root). Accordingly, the plant identification was done in the field by botanists from the Museum of Natural History of the National University of San Marcos (UNMSM), Lima, Peru (Sebastián Riva and Jean Salcedo). Regarding the measurement of the plant traits (nitrogen, LDMC, phosphorus), we only collected the minimum amount necessary for the analysis, collecting only the leaves directly from the plants in the field, and trying to be as minimally destructive as possible for the experiment.

Then, to infer the effect of the llamas on soil development (i.e., Hypothesis 1) in May 2019 (before introducing the llamas) and June 2022 (three years after initiation), we collected three soil samples distributed in the upper, middle, and lower slopes of each llama plot. Each sample is itself a composite of three subsamples collected within 1m2, between 3 to 15 cm deep. We excluded from the sampling any pure organic surface layer, litter, and vegetation (cf. Appendix 1 – Field data collection).

Additionally, we collected data of covariate variables that might potentially affect our response variables: subplot slope degree and soil temperature. To measure soil temperature, we buried two HOBO 8 K Pendant data loggers (five to 10 cm depth) per plot within the upper and lower parts of the plot. Since June 2019, the 24 data loggers have recorded temperature every four hours. The slope and soil temperature measurements allowed us to account for confounding factors such as a slope effect on soil composition (i.e., Hypothesis 1) or vegetation cover (i.e., Hypothesis 2) or an effect of the proximity of the glacier on soil temperature. We used the available precipitation and air temperature data produced by the ANA (Autoridad Nacional del Agua, Huaraz, Peru) from a weather station installed within the Uruashraju glacier foreland) to corroborate our soil temperature analysis and infer the role of seasonality on the response variables (Figure S2).

Finally, to estimate the fertilization effects of the llamas on the soil composition and their role as seed dispersers (i.e., Hypothesis 3; Fig. 2d), we collected three fecal samples from three different llama dung piles in each llama plot. The Environmental Quality Laboratory (EQL) in Huaraz, Peru analyzed samples for nutrients, and the Museum of Natural History of the UNMSM in Lima, Peru analyzed seeds in the samples (cf. Appendix 1 – Field data collection).

Laboratory and herbarium method

Laboratory analysis

To infer the role of llamas on pedogenesis, we analyzed soil pH, particle size distribution, soil organic (SOC) and inorganic (IC) carbon, soil nitrogen (N), and carbon isotopes (δ13C). We analyzed the 48 soil samples at the University of Texas at Austin, USA, mostly at the Soils and Geoarchaeology Laboratory. Soil pH was determined using a soil:solution ratio of 1:2. Because estimating SOC in proglacial soil is complex (due to low SOC and carbonate or clay contents), we used two different methods: sequential Loss On Ignition (LOI) and Elemental Analyzer (EA). First, we analyzed the 48 samples from 2019 and 2022 using the LOI method for SOC and IC (cf. Appendix 1 – Laboratory analysis). Second, for the 24 samples collected in 2022, we measured SOC and 13C by isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Values of δ13C provide information about the origin of the SOC. Bardgett et al.57 linked high δ13C values to the presence of ancient carbon, and Kielland and Bryant21 used δ13C values to examine the effects of herbivory on soil carbon composition. We measured N using an EA CHNS-O. Finally, at the Laboratory for Environmental Archaeology of UT Austin, we performed Particle Size Analysis (PSA) after deflocculation (cf. Appendix 1 – Laboratory analysis).

The EQL in Huaraz, Peru measured leaf LDMC, N, and P, as well as the total organic C, total N, and total P of the fecal samples. We measured LDMC only for P. prostrata and S. sublutescens since we did not expect major changes within the tussock grasses58. N and P were measured for all species. At UNMSM in Lima, we evaluated the viability of the seeds using the Tetrazolium test (Table S22; cf. Appendix 1 – Laboratory analysis).

Data analysis

Data analyses were performed using the statistical software R version 4.2.2. To test our first hypothesis (i.e., llamas catalyze soil formation), we first computed summary statistics for all the soil response variables (texture, pH, SOC, IC, N, and δ13C) for the control and llama plots. Afterward, we used linear models to test the significance of the variation assignable to the llama treatment. We included as response variables texture, pH, SOC, IC, N, and δ13C. We used a fixed blocking factor (4 blocks) to control for time constant unobserved effects within each block (Fig. 2), and “Treatment” and “Years” as fixed factors. We first ran a model based on the experiment’s full three-years (including samples from 2019 and 2022). Second, we ran two separate models, one for the 2019 data and one for the 2022, to remove the variable “Years” from the model to gain degrees of freedom and reduce standard errors. Since the soil nitrogen data from 2019 and 2022 are not comparable because of different drying methods, we did not run the full 3-years model on soil nitrogen. We report the results of all models within the results section and supplementary material.

To test our second hypothesis, we assessed plant community changes based on species richness—count of species per subplot to estimate the taxonomic diversity of the subplots, plant cover, and plant functional traits (i.e., LDMC, N and P, plant height, necromass, and greenness) between the control and llama plots. Plant height and necromass were community weighted for each subplot. As well, we calculated a percentage change in plant cover between 2019 and 2022. First, we computed summary statistics. Then, as for the soil data, we used linear models with a fixed blocking factor to analyze the effect of llamas on plant cover, height, and necromass. The linear models for the vegetation response variables included “Treatment”, “Years”, and “Block” as explanatory variables. In addition, the initial plant cover values reported in 2019, were used in the plant cover analysis as a co-variate to increase the power of the test. We computed the total percentage cover of each species for the overall experiment to select the four species most representative of the plant community. Then we ran distinct models for the four species to test for the effects of the llamas on the species selected. We used Generalized Linear Models with a Poisson distribution to test the effects of the llamas on plant richness and greenness because both variables were discrete, and we hypothesized that species richness patterns were scattered during the first stage of primary succession (i.e., species not aggregated). To evaluate differences between years and between control and llama treatment, when relevant (i.e., Plant cover and Greenness), we computed pairwise comparisons using the emmeans package with Bonferroni corrections (emmeans function). Afterward, we used linear regressions to assess the effect of the initial subplot cover on the percentage change in cover between 2019 and 2022 and the 2022 plant cover. We log transformed the variable Plant Cover to increase the fit of the model (Shapiro–Wilk normality test: p-value = 0.094, W = 0.988; Breusch-Pagan test: p-value = 0.46; Chi-square = 0.547). We computed all the linear and generalized linear models using the lm and glm functions of the stats library and the model fit diagnostics were checked using the DHARMa package.

To analyze variation in soil temperature we used the period with complete data from 23.06.2019 to 22.05.2021. We calculated summary statistics and used Wilcoxon tests to assess the difference between control and llama treatments. To infer differences in air temperature that might have affected our response variables we compared mean daily temperatures over three periods corresponding to our field evaluations dates: June 2018 to May 2019; June 2019 to May 2021, and June 2021 to May 2022. We used ANOVA and Tukey Honestly Significant Difference tests to assess differences between the three periods. Finally, we tested for significant differences in slope gradient and granulometry of the subplots between the llama and control plots with T-tests and Wilcoxon tests (ggpubr library).

Crédito: Link de origem

Comentários estão fechados.